Freedom, Envy, and the Price of Meaningful Work

When fragmented institutions ask for our whole selves they get fools they didn't deserve and often can't handle.

You may know this feeling: You're praised for your commitment, recognised for your contributions, maybe even held up as an example of what the organisation needs more of.

But the moment your work becomes either too heartfelt or too transformative - something shifts.

The praise wanes. The topic shifts when you approach old colleagues.

It’s not failure that’s unsettling things. It’s a kind of success that stirs up what we’ve collectively agreed to keep below the surface.

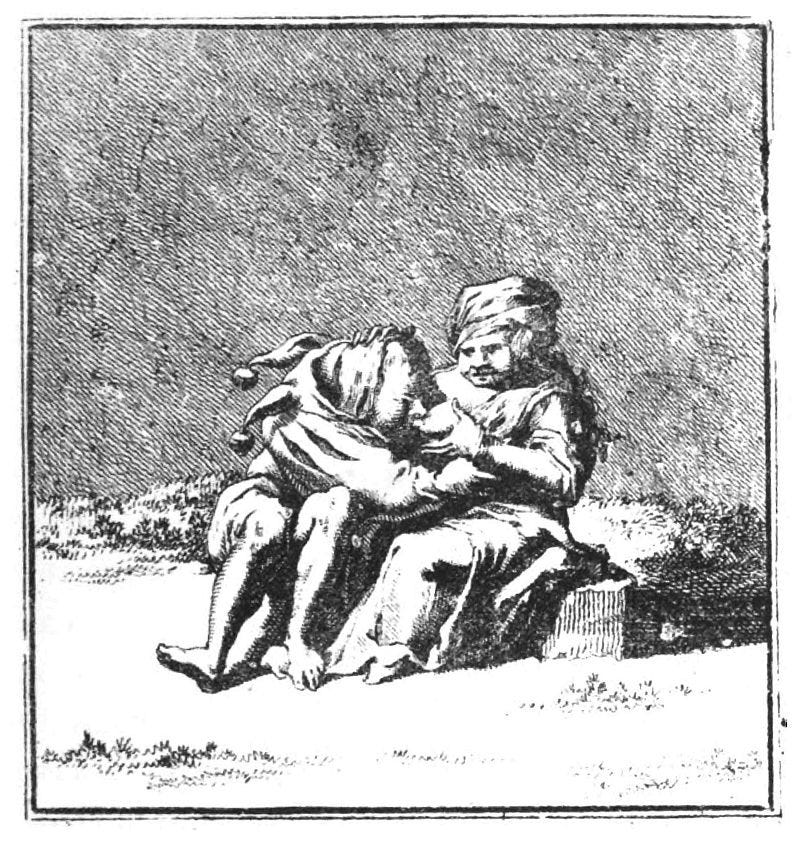

Like the medieval court jester who had permission to speak truth because they wore the bells of folly, these individuals succeed not despite their wholeness but because of it. And that kind of success - that freedom to be authentic in spaces designed for performance - becomes the very thing that makes them dangerous.

In many institutions, especially those with strong values and noble missions, the people most admired are not always the most powerful, but those who bring a kind of freedom born from inner commitment.

They act from integrity, not performance. Their presence reminds us of what we once hoped work could be.

And yet, those same people can unsettle us.

Because the more they show up whole, the more we must face the ways we’ve adapted, armoured, survived. Their sincerity can feel like a mirror we didn’t ask for.

These are the fools and jokers, in the oldest sense: the ones who offer their hearts to work that matters.

Not as martyrs, but as what Erasmus recognised as the wisest fools - those who know themselves to be foolish yet persist anyway. William Blake saw the alchemy in this: "If the fool would persist in his folly he would become wise" was one of his Proverbs of Hell.

They don't retreat when their belief in meaning is mocked as naive. They lean in, knowing that what the world calls folly might be the only sanity left - that acknowledging our foolishness, as Erasmus claimed, is the highest wisdom.

And institutions, like all human systems shaped by hope and by fear, sometimes struggle to make room for that kind of belief. Not because they’re malevolent, but because we are afraid of what it might require.

⸻

The Fool's Heart

“First of all, this prince is an idiot, and, secondly, he is a fool – knows nothing of the world, and has no place in it.”

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot

Many of my students speak of wanting work that feels purposeful and meaningful. I usually ask: Who will be the author of that meaning?

And almost inevitably, they first look outward: to an organisation, a role, a mission. As we’re taught to do.

But if meaning is something we wait to be given, we remain at the mercy of systems never designed to carry our full humanity. The deeper truth is harder: meaning, if it is to be real, must be risked and authored from within.

The Fool is the one within us and, those amongst us, who still dare to believe that work can be sacred, that relationships can be real, that institutions might serve something larger than their own continuation. Not because they’ve found the perfect place to do it, but because they’ve decided to show up that way anyway.

In organisational life, these Fools are often the quiet healers. Teachers who transform. The leaders whose care disarms cynicism. The colleague who creates the safety others need to try again. They heal not through power or technique, but through presence to their inner truth and sincerity.

When someone shows up whole, it reveals the ways the rest of us have contorted to survive. Their nakedness isn’t shaming, it’s confronting. Their capacity to find meaning in even the most tedious work exposes how much we’ve had to numb, or never known how to seek.

The Fool isn’t a rare type. It’s a part of all of us. One we often hide, suppress, even mock in others, because we’ve learned it’s safer that way.

But perhaps that hiding is functional. The fool part of us doesn't emerge from naivety but from necessity to maintain connection to meaning when the systems around us can't provide it. It's not idealistic but adaptive: a method for keeping some part of ourselves alive in spaces that reward fragmentation.

We mock it in others because we recognise the risk we once took, or still take, in keeping that part of ourselves breathing. The Fool represents not purity but persistence and the stubborn refusal to let meaninglessness have the final word, even when showing up whole feels dangerous.

When organisations turn away from those who insist on wholeness, it’s not always a calculated rejection. Often, it’s the ripple of our shared discomfort. The fear that if we said yes to that kind of sincerity, we might have to change. Or feel. Or remember something we let go of too soon.

Systemic Envy and the Regulation of Freedom

“It is better to be unhappy and know the worst, than to be happy in a fool’s paradise.”

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot

Melanie Klein's insights into envy illuminate what happens when institutions encounter those foolish enough to access meaning without seeming to pay the conventional price. Envy isn’t just wanting what another has - it’s the impulse to spoil or reject what’s good because we fear we can’t have it ourselves.

But perhaps we don't truly know what to envy, just as we don't know what to desire until we witness what others admire and recognise. And then when that is denied to us, but also that denial remains devoid of meaningful explanation, we turn the envy towards the fools who seem to be happy regardless of recognition. Often despite it.

If Klein and Lacan were to meet, they might blame Nietzsche for this state of affairs. And how the resulting spiritless world redirected our fury toward individuals who must now bear the burden of what once belonged to the sacred. In the absence of the containing ideas that once made sense of hierarchy and suffering, we are left with only individuals to blame. And we remain alone to seek the foolishness within.

In modern institutions, we often project these sacred longings onto structures and expect them to deliver purpose, love, belonging. But institutions don’t generate meaning. People do: We do. Or we don’t.

So when someone finds a way to offer their work with freedom or love, it disrupts the uneasy compromises we’ve come to accept. Their sacrifice, for that’s what it is, can seem both inspiring and unbearable.

Those who access meaning without 'playing the game properly aren't given bells to wear, instead they're often shown the door. We envy not just their freedom but their refusal to pretend that freedom must be earned through suffering. They reveal the lie we've been living: that freedom was always available. We just believed we had to suffer for it first with years of climbing ladders, or by enduring toxic bosses, suppressing parts of ourselves, and “paying our dues”.

Our response is rarely overt. We rarely punish, more often we quietly withdraw our affiliation. We create distance. We stop extending invitations. The message we send is subtle but clear: you've stepped outside what we know how to hold.

This isn't malice. It's our collective fear that if we opened to that kind of freedom, we'd have to reckon with what we've traded for safety.

What We Learn from the Exiled

And what if the people we quietly exile are not dangerous to the work but vital to it? What if they aren't threats but early messengers? Not misfits, but signals of what we can't yet hold?

Their journeys (that Fools usually go through) often reveal less about their limitations and more about the thresholds we fear to cross. Toward wholeness, change, or care.

Like Jacinda Ardern's 2023 resignation : a leader who embodied the kind of empathetic leadership the world claimed to want only to offer a backlash.

We see it again and again. The teacher who brings too much heart. The colleague whose integrity disrupts the group’s equilibrium. The leader whose gentleness is mistaken for weakness. The pattern isn’t personal - it’s systemic. And it’s shared.

Because when we exile we mark a moment when we could not, or would not, accept and make sense of something new. Something that asks more of us than we know how to give, at least for now.

But in the wake of their departure there is an invitation. To ask not just, “Why did they go?” but, “What in us could not stay with them?”.

What did their presence reveal about the compromises we've made? What freedom did they embody that we've learned to fear?

We often discover that we miss them only after they're gone. Not just their contributions, but the permission they gave us to remember parts of ourselves we set aside.

Their exile shows us the limits of what we’ve built. And, sometimes, the beginnings of what might possible.

A Different Kind of Success

“The prince assures us that beauty will save the world!”

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot

True success may not be about taking power but about refusing the inherited split between being whole and surviving. It requires mourning for the institutions we hoped to find, or for the (idea of) love we feared we'd lose by showing up whole.

But it also requires faith: that the parts of us we've exiled may be the parts most needed to heal what we've built.

When we recognise that the system's wound is ours, that every exile is a mirror, then even betrayal becomes a portal back to each other.

Each exile traces the Fool's Journey from the Tarot - the one who walks toward the cliff edge, dog nipping at their heels, trying to warn of danger they already see. But the Fool is both the beginning and the end of the journey. Those we push out often return as the very wisdom we need.

The exile was never failure - it was initiation.

Loved the depth and insights of the essay Wojtek. I have a further question does this totally excuses companies of not providing meaning and soul. There must be "fool" companies somewhere ?

Thank you for writing this. Something shifted in me in a positive way!